US borders closed as New World Screwworm threatens livestock industry

The New World Screwworm has become a significant concern among livestock farmers in both the US and Mexico. In the US, there are growing worries that the pest could spread northward and threaten the multi-billion dollar livestock industry. Following recent cases reported in Ixhuatlán de Madero, Veracruz, Mexico – 370 miles south of the US-Mexico border – US agriculture secretary Brooke L. Rollins has closed southern border ports to livestock trade in an effort to halt the spread.

Due to this further northward spread of the New World Screwworm in Mexico, Rollins announced the closure on 9 July after Mexico’s National Service of Agro-Alimentary Health, Safety, and Quality (SENASICA) reported a new case of New World Screwworm in Ixhuatlan de Madero, Veracruz, Mexico, on 8 July.

This new northward detection comes about 2 months after northern detections were reported in Oaxaca and Veracruz, less than 700 miles away from the US border, which then caused the closure of ports to Mexican cattle, bison, and horses on 11 May 2025.

The USDA initially announced a risk-based phased port re-opening strategy for cattle, bison, and equine from Mexico beginning as early as 7 July 2025, however the USDA noted: “This newly-reported NWS case raises significant concern about the previously reported information shared by Mexican officials and severely compromises the outlined port reopening schedule of five ports from 7 July to 15 September. Therefore, in order to protect American livestock and our nation’s food supply, Rollins has ordered the closure of livestock trade through southern ports of entry effective immediately.”

How exactly is the New World Screwworm a threat to livestock?

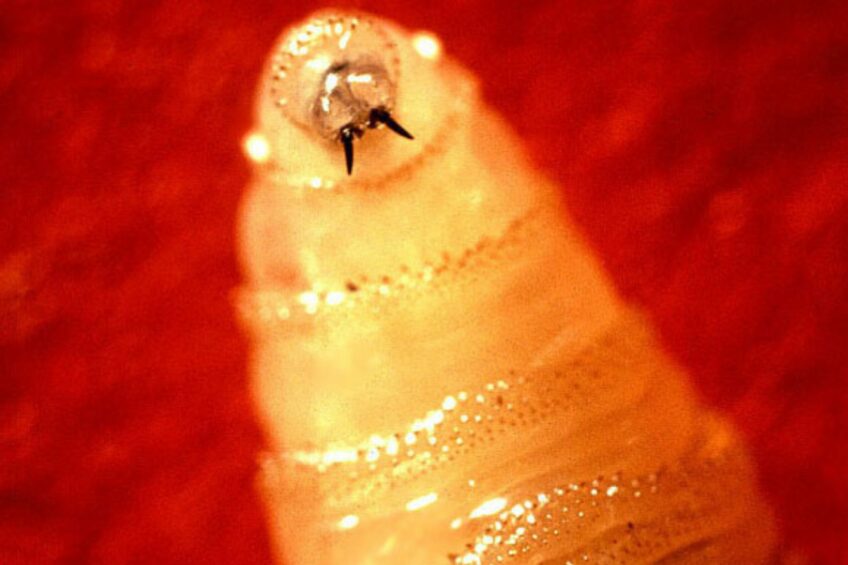

The New World screwworm (Cochliomyia hominivorax) is a blow fly native to the western hemisphere. Adult female screwworms are attracted to wounds and lay their eggs on living mammals. The larvae then burrow into fresh wounds or body orifices of livestock, including horses, cows, and bison.

According to the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH), the adult female fly lays approximately 300 eggs at a time. The larvae emerge within 12-24 hours and immediately begin to feed, burrowing head-downwards into the wound. They can cause serious, often deadly damage to the animal.

The eggs develop through 3 larval stages involving 2 moults. The larvae then leave the wound and drop to the ground, where they burrow to pupate and later emerge as adult screwworm flies. The duration of the life cycle off the host is temperature-dependent, being shorter at higher temperatures. According to WOAH, the entire cycle may be completed in less than 3 weeks in tropical regions.

Eradication of New World Screwworm in the US

This is not the first time the US has had to deal with the New World Screwworm. In the 1960s and 1970s, it was eradicated by breeding sterilised males of the species and releasing them from aeroplanes to mate with wild female flies. This eventually reduced fly populations by preventing females from laying more eggs. This strategy of releasing sterile males is still in use today.

The USDA stated: “We use a biological control technique (sterilised insects) to eradicate New World Screwworm fly populations. This approach eradicated New World Screwworm from the US in 1966 and eliminated a small outbreak from the Florida Keys in 2017.”

New World Screwworm is endemic in Cuba, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and countries in South America. For decades, the US and Panama collaborated through the Commission for the Eradication and Prevention of Screwworm (COPEG) to prevent the pest’s northward movement, according to the USDA.

“The United States has promised to remain vigilant, and after detecting this new New World Screwworm case, we are pausing the planned reopening of ports to intensify quarantine efforts and target this deadly pest in Mexico. We must see additional progress in combating New World Screwworm in Veracruz and other nearby Mexican states before we can reopen livestock ports along the southern border,” said US Rollins.

A pricey battle

Combatting this pest and protecting the US does not come cheap. Rollins announced on 18 June that it launched an US$8.5 million sterile New World Screwworm fly dispersal facility in South Texas, and announced a sweeping 5-pronged plan to enhance the USDA’s already robust ability to detect, control, and eliminate this pest.

In addition to the fly facility launched in Mexico, the USDA also spent US$21 million on renovating an existing fruit fly production facility in Metapa, Mexico, which will provide an additional 60-100 million sterile flies a week to stop the spread, on top of the over 100 million already produced in Panama. This will result in at least 160 million flies per week.

Furthermore, a USDA report indicates economic losses in the billions of dollars. “This work was based on a past outbreak in Texas with dollar figures updated for inflation. Any outbreak in Texas or other parts of the US would require large increases in labour costs on ranches as producers will have to constantly inspect and treat animals. Production costs would increase sharply for ranchers in impacted areas,” David Anderson, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service livestock economist, told Dairy Global.

Anderson added: “We are already seeing economic impacts – not from the screwworms, since we do not have them yet, but because of the border closure to feeder cattle from Mexico. The shortage of those cattle is starting to show in reduced fed cattle slaughter and lower beef production, leading to higher prices.”

From an economic standpoint, he noted: “Damages will likely be greater in a faster-spreading infestation. Other animal disease outbreaks indicate that the time to discovery, treatment, and containment is critical in reducing the economic impact of the occurrence. I expect screwworm infestations would be the same. A faster-moving outbreak that covers more area would cause greater losses.”

It is clear why major efforts are underway to stop the spread into the US. Keeping New World Screwworm out of the US is crucial to protect the livestock industry, the economy, and the food supply chain, stated the USDA. “The United States has defeated NWS before and we will do it again,” Rollins commented.

Join 13,000+ subscribers

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay updated about all the need-to-know content in the dairy sector, two times a week.