Milk fever, or hypocalcaemia, is a common condition, especially in high producing dairy cows, which occurs when a cow does not have sufficient blood calcium levels. It is a common metabolic disorder post-calving, usually within the first 24-hours post calving. At the start of lactation to produce colostrum, the calcium demand is almost doubled, therefore a significant requirement is seen. As a result, about 80% of milk fever occurs within one day of calving and can still impact 2 to 3 days post-calving. When the cow cannot meet the increased demand for calcium, this results in lowered blood calcium concentration and milk fever. Although all cows are susceptible to milk fever, Jersey cattle have a higher risk for the occurrence of milk fever than other breeds, according to research. It can be either clinical (severe calcium deficiency) or subclinical (perform much less efficiently due to an underlying calcium deficiency).

Milk fever

Correct calcium levels are vital and it is essential for proper body functions. It is particularly important for the nervous system and muscle cells and plays a key role in muscle contraction. If the calcium content in the blood is too low, the muscles can no longer contract. When this happens, the cow cannot move or stand up. Milk fever has been associated with higher risk of; dystocia, uterine prolapse, retained placenta, mastitis and displaced abomasum, decreased milk production, decreased immune function, increased risk of ketosis and decreased reproductive performance. In terms of detection, mild cases may not be easily visible, however there is still an impact on productivity. If the signs and symptoms are not detected, in the longterm calcium deficiency can lead to cardiac arrest and death.

There are different stages in which milk fever occurs. The symptoms can therefore be categorised in 3 different stages.

During stage 1 signs can go unnoticed because it only lasts for about 1 hour, signs include weakness, nervousness, a decrease in appetite, and hind feet being shuffled.

During stage 2, which can last anything between 1 and 12 hours, a cow is weak and lethargic and will have its head tucked into its flank as a characteristic milk fever posture, will not be able to stand, while trembling and constipation can also be seen.

During stage 3 the cow will not survive more than a few hours, so treatment as fast as possible is imperative, signs include lying down, not being able to stand up and loss of consciousness which can lead to a comatose state and death.

The diet of dry cows for approximately 2 weeks before calving should be monitored carefully, taking note that the proper levels of calcium is available before and after calving. Ensuring to limit calcium intake to less than 100 g/cow/day and phosphorus intake to less than 45g/day for2 to 3 weeks before calving. Forages high in calcium like alfalfa should be avoided. Instead think of, grass hays, cereal silages and corn silages. Potassium levels should be less than 1.5%, as forages low in potassium are low in calcium. Anionic salts can be an effective way of lowering the incidence of milk fevers.

Magnesium can also play a significant role in the prevention of milk fever, for efficient absorption and resorption of calcium. Therefore, supplementing with magnesium about 2 to 3 weeks pre-calving will reduce the risk of the occurrence of milk fever. However, continued supplementation will be required during early lactation.

Once the cow has calved, it needs to have adequate calcium intake during milk production. Cows should be given dietary calcium during the colostrum period, which can be done through dusting of pastures, or by including it into supplements being fed.

Treatment

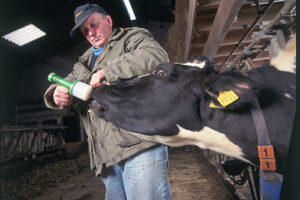

As treatment, some veterinarians will advise on oral administration dose of a calcium salt in a gel. Alternatively, an orally administered bolus containing a much higher concentration of calcium than the injectable solutions can also be administered, however in this case the cow should be standing or sitting up. If the cow is lying down flat then immediate intravenous therapy is required to avoid death. When milk fever is suspected, it is important to seek help quickly. Treatment options include calcium injection by intravenous, intramuscular or subcutaneous routes.